My threshold of craziness is much lower-- the most unreasonable I get is in the mad-dog pursuit of surf by sailboat.

Instead of spending Thanksgiving in a cozy living room with the laughter of family, four of us cast off from Avalon harbor in Catalina, and headed 20-some nautical miles into the ocean, under a canopy of dark clouds boiling ahead of a storm.

Instead of spending Thanksgiving in a cozy living room with the laughter of family, four of us cast off from Avalon harbor in Catalina, and headed 20-some nautical miles into the ocean, under a canopy of dark clouds boiling ahead of a storm.As we pulled into the navy island of San Clemente, there were no helicopters, or ships with live fire, or other signs of the war machine. The only thing blasting into the island was a huge groundswell.

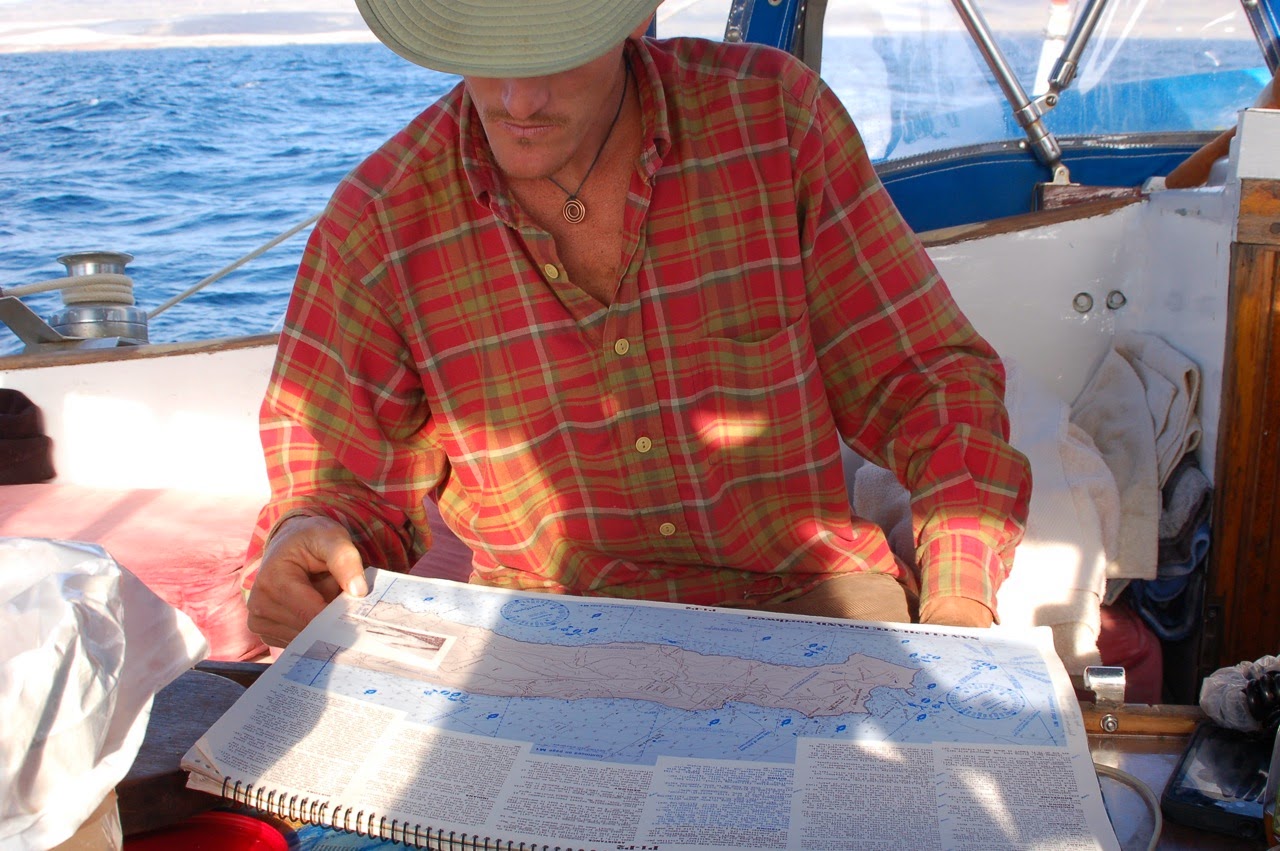

We anchored in a large cove with swells moving through 40ft of water. Billowing plumes blew off the waves with a south-east wind -- an indicator of an approaching front. Yet, shafts of light shone on the ocean surface, with a thinning cloud cover.

My girlfriend Sabrina looked at me hopefully - maybe it would clear up? In full disclosure before the trip, I had optimistically said that there was a 50-50 chance we'd get rain. My buddy Alex played along, with his characteristic cheaky grin, "I think we could get lucky - one way or another!"

Chris was less buoyant, and wanted to get down to business: "Are we doing this, or what?" he said, pulling a wetsuit out of the locker. The conditions were stable; this was our chance.

What followed was a magical afternoon. When all the elements come together in surfing, it is deeply gratifying. Tide, wind, swell, light, sea lions, us. It was one of those blissful moments when everything "lines up".

Isn't this what we are all looking for? When life seems just right, feeling total connection in an effortless flow, whether for the basketball player "in the zone" or a mother holding her newborn baby; or Alex, in this case, riding through a heaving tube and declaring his trip was already complete.

Back at the boat, Sabrina made a Thanksgiving meal fit for kings. Half a roast turkey in the boat oven, homemade cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes and all the trimmings.

In all the baking and exuberance, the sous chefs failed to notice the wind was increasing. When the pitter-patter of rain began on the canopy, Chris unzipped the curtain and looking out into the dark anchorage. The lights of the Navy base were dim in the distance, and he recoiled. "Damn it's cold outside!"

At this point, I had the brilliant idea of firing up our wood-burning stove, which we had just "fixed" the week prior, to my eventual chagrin. That little stove had treated us graciously for years, up until that fateful night.

In a classic moment of not-knowing what you don't know, I had recently fixed the leaky chimney flu with epoxy, as I do with all repairs on the boat. Unfortunately, I forgot to take into account that epoxy catches on fire at a certain temperature.

Suffice to say that I had the opportunity to try the fire extinguisher in a real emergency for the first time. I'm happy to report it worked! Besides cleaning the extinguisher mess, all we had to contend with was 20 minutes of fumes as we aired out the cabin, along with some unwelcome rain as we enjoyed our pumpkin pie.

When the air was clear, we slept with our full tummies and the steady drone of rain, confident in the 66lbs Bruce anchor and 230 feet of chain holding us in place.

A radical change occurred at 10am the next morning, which I thought, was a very civilized hour for the storm to kick into gear.

At that point, the wind shifted and began pushing us towards shore; Aldebaran copping the wind chop on the nose, suddenly turning this peaceful cove into a lee shore, an unprotected anchorage.

The rain had started pounding, but there was no choice -- it was time to go sailin'.

Third is Robby Seid, who is a traveler, fishes salmon in Alaska, and works in mechanical design. Every time he comes aboard Aldebaran he improves the boat -- whether it's the sunglass line, the guitar rack, or just a roll of non-skid tape. We met on the Oaxaca coast and I'm glad we stayed in touch.

Third is Robby Seid, who is a traveler, fishes salmon in Alaska, and works in mechanical design. Every time he comes aboard Aldebaran he improves the boat -- whether it's the sunglass line, the guitar rack, or just a roll of non-skid tape. We met on the Oaxaca coast and I'm glad we stayed in touch.